What is an ethnographic interview?

- IF anthropology is the study of what we (humans) do and say and think and mean, and IF we cannot read minds… THEN the most ethically correct (and also effective, efficient, etc.) way to get at the thoughts and beliefs and understandings of other human beings is by asking them, in addition to observing them, thereby allowing real human beings to have real voices and a real say in what and why and how they do and say and think as they do.

“Man, drag queens are a unique bunch,” I think to myself. And I’ve done a solid amount of participant observing among them in pageants and shows for years. I can even arrive at conclusions based on my observing:

“It seems to me that their decision to do drag are decisions to pursue their passions, despite the economic and social risks which still exist today. I mean, they talk about the importance of doing what you love and stuff all the time.”

I continue thinking: “And yet… it seems to me that they share a strong sense of uncertainty (uncertainty of their own future economic stability, in particular), and this uncertainty, it seems to me, can mitigate their excitement for their work and their confidence in themselves. Not always. But often. And they seem particularly pessimistic when discussing society and culture and all the drama with each other.”

All of this leaves me considering: “Is there a paradox here?

Okay, maybe I am being obvious. Or: maybe my thinking is wrong-headed. Regardless, I have just described a series of thoughts I induced based solely on my observational experiences overhearing conversations at pageants.

- Now: you’re a drag queen. Do you feel voiceless and/or annoyed? Like, “Why is she inducing instead of asking me? Just because she hangs out at our events…” This is what being observed without being asked feels like.

Also, don’t I seem stuck in my questioning and like I might advance much faster to some answers if I sit down and talk to you, several of you, already?

I must, necessarily, talk to my informants (the queens, at least some of them) in contexts and spaces which allow THEM to tell me how THEY think about and understand themselves, their futures, and more, if I really want to trust my findings related to THEM. Depending on what THEY tell ME, I can then strengthen or refute my initial hypothesizing and then add further lines of questioning to my research. See how that works?

Science is a practice (the loop)

- Ask, investigate, analyze, find … do it all over again … In all that one asks, as a scientist, one aspires to collect multiple lines of evidence.

- Participant observation, obviously, provides various lines of evidence. But so, too, does the ethnographic interview. The interview allows you to check your observations and interpretations with the very individuals you are observing.

So what does one ask in an interview?

- Americanist sociologist Howard Becker said, “scratch the ‘why’ questions and focus on the ‘how’ questions” (my own paraphrase). Let me show you why he said this:

Pretend I ask you, “Why do you do drag?”

- Do you feel like I just put you on the defensive? Maybe? Like I just asked you to explain your decisions to me, as if I (who does she think she is?!) deserve an explanation from them, and also, maybe, am I coming off as a self-important asshole-interlocutor (is she implying drag is stupid in that question?).

- Does it seem as if I might be wasting their time when they have little to no time to give, and so now they have no intention of providing me with lengthy or “thick” or even sincere answers? Perhaps you are more forgiving than this, but others will not be.

Next: what if I had asked, instead, “Can you tell me about how you got into drag?”

(Reread the why question. Now the how. And now the why again).

- Can you see how, in this latter case, I am a different person? A different (more likable, more relatable, perhaps) kind of interviewer? Assuming I chose the right tone, I am asking you for information in a way that:

- does not put one on the defensive, and

- makes me appear as if I respect them and their time and sincerely value your answers and want to know more about you and your lived experiences and your thoughts, etc, etc.

- Further, by asking how, I am giving them a chance to give me especially concrete feedback. with “How did you get into drag?” Here each of my interlocutors is likely to have their/her/his own story to tell.

All of THIS is why I say drop the “why?” questions; rewrite them as “how?” questions.

Here’s another example,“Why do drag queens use the word whore?”

How would you and those around you respond?

What if you were asked, instead: “How is ‘whore’ used in the drag world, and/or by queens, today? Can you think of any examples?”

- Which question invites you in?

- Which encourages you to open up, and to speak most concretely (provided you have something to say), borrowing from your real experiences and understandings?

- Which question will get me (the interviewer) the better, more concrete answers? (The latter question does these).

Building rapport while asking questions

In short, you want your interlocutors to like you.

- In the end, the kinds of data that reflect communities or societies most accurately need to be representative of the individuals within those communities or societies.

- Building rapport from within the interview, becomes especially important within those contexts in which we are speaking with strangers or near-strangers.

- On an individual by individual basis, think about what you know about your informant, and what you believe will make that person most comfortable.

- What do you need in order to achieve this level of comfort for that individual?

1. Consider the time and place of your interview.

2. Think about your own presentation of self: your dress, posture, tone and voice (including your emotive performances as well as your word choices), non-verbal gestures, and more. Think about the *vibes* you want to send and how you will achieve this.

- In my fieldwork in Yucatan and Guatemala, for example, I adopted a formal discourse and highly structured line of questioning when speaking with politicians and investors who made it clear (via their dress, speech, spending habits, and more) that they privileged efficiency and professionalism. I ran these interviews in their office spaces, brought them coffee, and I smiled and told them not to worry, no hurry, each time we were interrupted by a coworker or secretary. I made clear that my interest in their lives was a professional, scientistic interest.

- With Mayan curanderos (healers), in contrast, I tried as hard as I could, to come off as empathic, excited to be in conversation, personally interested/invested, and casual/relaxed: as opposed to overly rigid or academic. (To be clear, these performances of mine were always sincere.) I ran these interviews in their homes, or in public plazas, and often offered to (and later did, in several cases) babysit their children (an attempt at reciprocity that was more meaningful than gifting coffee to these women) and buy everyone sodas and sometimes special snacks I knew they liked. Just like in my more formal interviews, I told the curanderos not to worry whenever we were interrupted — by clients/customers or neighbors or kin and fictive kin in these cases.

- Even when “interviewing” via email (or other digital interface), building rapport remains key. Before you begin, obviously, you must decide who is and isn’t comfortable using email as a medium of communication. Or who checks email rarely and thus will miss your request. Who hates typing? Who doesn’t read? If you only use emailed interviews, whose voices are you excluding from your study? What the etiquette even is for communication!

- Once you’ve decided to use email, you must show your emailed interviewee you care about his/her/their replies. You can do this by choosing a tone that is friendly/warm. Also by adapting your style to your interlocutor, as I just modeled above.

- We call this technique "approximation" --- it allows the interviewer to change their presentation to fit their audience as a sign of respect and a desire to make communication more facile.You must know, be able to empathize with, and respect (you figure out how / for what reasons) your audience if you want them to take you and your interview, email-based or not, seriously.

Summary

- To every ethnographic interview, you arrive with a plan, a list of questions, sure, but you adapt that plan as the interview evolves.

- Your interlocutors’ positions, practices, and expectations shape your rapport building strategies. So, too, do the contexts in which you are interviewing.

- Are children present? Snoopy neighbors? A secretary or boss? You might modify your tone and voice within an interview. And you will continually accommodate to make more comfortable your interviewees.

- In the end, the strongest ethnographic interviews are those that are appropriate and inviting. They are dynamic, changing in an instant as the context in which you interview changes, rather than rigid and unwavering. We call them “Semi-structured" or “informal.”

- Are they messy (and sometimes even stressful)? Absolutely. But this is the most ethically correct and effective way to run an interview at present.

- prioritize questions

- throw out questions that do not serve your scope of research (there is always another project!)

- semi-structured interview still allows for informants to talk and keep talking until they are finished

- allow informants to speak until they are finished

- follow up with questions which get informants to elaborate on their previous answer (this requires that you listen and think about what they are saying)

- only move on when you have exhausted the scope of the informant's answer

- transcribe your notes

- emic presentation: the meanings people give to their actions and the world around them form an essential component of understanding.

- informants can be eloquent communicators about their culture

- information on secret histories, internal power struggles, unofficial customs

- an opportunity for private discussion that can reveal beliefs and opinions difficult to access otherwise (things people will only discuss in a one on one interview)

- good way to enter a fieldsite, gain trust, and gather basic information

- developing trust and rapport or build a deeper connection

- prompting in-depth responses

- ask for information about others and possible leads

- reveal cultural logics or conflicting reports reveal different meanings or contested meanings within the culture

- different versions reveal the ways that individuals vary within the collective

- ask informants if they have any questions for you at the close of an interview, or "what else should I know?"

- virtual worlds may be textual rather than auditory with fewer conversational cues like tone, volume, inflection, posture, or gaze

- harder to determine who is speaking to whom or nuances of meaning

- fast typing skills are needed

- may be multiple conversations going on

- choose closed session interviews like zoom or skype or messenger or facetime or google rooms

- create new social situations and can be held to ask group questions

- help each other with prompting and recall

- eases awkwardness

- allow for comparison

- minimize observers bias

- see how cultural values and social relations become apparent through conversation and interaction

- collect and correct memories to create oral histories

- be attentive to relationships and inequality between participants

- better if they already know each other (me)

- ethnographer is facilitators making sure everyone can speak

- ask quiet participant to respond directly

- do it as quickly as you can after your interviews so you can note nonverbal observations---take notes on this during interview if possible (i note time on recorder)

- word-for-word is best

- 4:1 (double if translating)

- ensure anonymity

- how to handle things like... (may reveal emotional content)

- hesitations (.)

- pauses : short or (2.5) time of pause

- laughter (laughter)

- unintelligible words xxxx

- video is better than audio

Tips on Transcription Practices for Linguistic Anthropological Analyses

Some considerations on transcription from Alessandro Duranti's Transcription: From Writing to Digitized Images:

We must keep in mind that a transcript of a conversation is not the same thing as the conversation; just as an audio or video recording of an interaction is not the same as the interaction. But the systematic inscription of verbal, gestural, and spatio-temporal dimensions of interactions can open new windows on our understanding of how human beings use talk and other tools in their daily interactions." (Duranti, 1999, p. 161)

A transcript is a technique for the fixing (e.g. on paper, on a computer screen) of fleeting events (e.g. utterances, gestures) for the purpose of detailed analysis.Transcripts are inherently incomplete and should be continuously revised to display features of an interaction that have been illuminated by a particular analysis and allow for new insights that might lead to a new analysis. (See Alessandro Duranti Linguistic Anthropology, Cambridge University Press, 1997: ch. 5)

There are different kinds of transcripts. Some transcripts are designed to only represent talk. Other ones try to integrate information about talk and gestures. Some other ones might focus exclusively on non-verbal interaction. Linguistic ethnographers often produce an annotated transcript, that is, a text where the representation of talk is enriched by contextual information that is relevant to talk or makes it meaningful.

Duranti's main points:

(i) transcription is a selective process, aimed at highlighting certain aspects of the interaction for specific research goals;(ii) there is no perfect transcript in the sense of a transcript that can fully recapture the total experience of being in the original situation, but there are better transcripts, that is, transcripts that represent information in ways that are (more) consistent with our descriptive and theoretical goals;

(iii) there is no final transcription, only different, revised versions of a transcript for a particular purpose, for a particular audience;

(iv) transcripts are analytical products; that must be continuously updated and compared with the material out of which they were produced (one should never grow tired of going back to an audio tape or video tape and checking whether the existing transcript of the tape conforms to our present standards and theoretical goals);

(v) we should be as explicit as possible about the choices we make in representing information on a page (or on a screen);

(v1) transcription formats vary and must be evaluated vis-a-vis the goals they must fulfil;

(vii) we must be critically aware of the theoretical, political and ethical implications of our transcription process and the final products resulting from it;

(viii) as we gain access to tools that allow us to integrate visual and verbal information, we must compare the result of these new transcription formats with former ones and evaluate their features;

(ix) transcription changes over time because our goals change and our understanding changes (hopefully becomes "thicker,") that is, with more layers of signification.

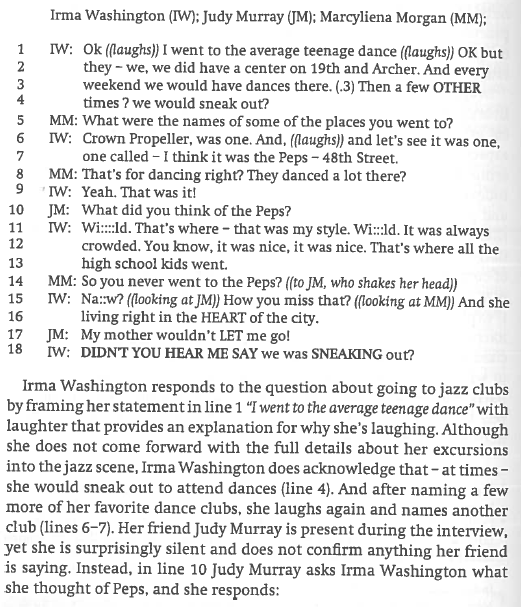

From Marcyliena Morgan's book Speech Communities, p. 94

Morgan chose to highlight only a few non-verbal signs to make her argument about the meanings of this conversation that were indirectly implied rather than directly stated (eg., noting instances of laughs, elongated vowels, eye contact, head shaking, and loud talking. Meanwhile, the numbered lines make it easier to refer readers to specific parts of the interaction.

To Try Your Hand at Transcribing:

Make sure to number your lines (either by using your word processor's number lines feature, or by manually numbering the utterances). For ease of reading, make sure to break up the interaction by speaker and utterance. Start a new speaker on a new line, and new utterances of one speaker on a new line. Select your transcription symbols from this chart adapted from Jefferson and Gumperz and Berlenz:

Symbol | Name | Use |

[ text ] | Brackets | Indicates the start and end points of overlapping speech. |

(1.5) | Timed Pause | A number in parentheses indicates the time, in seconds, of a pause in speech. |

(.) | Micropause | A brief pause, usually less than 0.2 seconds. |

. | Period | Indicates falling pitch. |

? | Question Mark | Indicates rising pitch. |

, | Comma | Indicates a temporary rise or fall in intonation. |

- | Hyphen | Indicates an abrupt halt or interruption in utterance. |

{f} | Brackets | Indicates that the enclosed speech was delivered faster than usual for the speaker. (G and P) |

{s} | Brackets | Indicates that the enclosed speech was delivered more slowly than usual for the speaker. (G and P) |

{hi} | Brackets | Indicates that the enclosed speech was delivered at a higher pitch than usual for the speaker. (G and P) |

{lo} | Brackets | Indicates that the enclosed speech was delivered at a lower pitch than usual for the speaker. (G and P) |

* word | asterisk | Indicates prominence or emphasis on the syllable (G and P) |

** word | asterisk | Indicates extra prominence or emphasis on the syllable (G and P) |

~ word |

| Indicates fluctuating intonation over a word or syllable (G and P) |

° word | Degree symbol (option 0) | Indicates whisper or reduced volume speech. |

ALL CAPS | Capitalized text | Indicates shouted or increased volume speech. |

wo:::rd | Colon(s) | Indicates prolongation of a syllable. |

(hhh) |

| Audible exhalation |

(.hhh) |

| Audible inhalation |

( text ) | Parentheses | Speech which is unclear or in doubt in the transcript. |

(( italic text )) | Double Parentheses | Annotation of non-verbal activity. |

No comments:

Post a Comment