Setting the Anthropological Table

| |

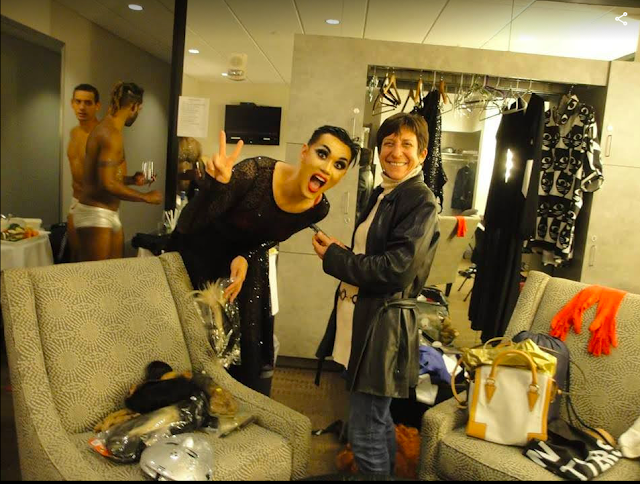

| Japanese food manga featuring the "superhero" and chef Sōma. Shokugeki no Soma is about a boy named Sōma Yukihira who dreams of becoming a chef. |

The anthropological approach to the study of food and foodways will present a set of methodological and theoretical tools to enable us to select , assess, "chew on", and mentally "digest" the significance of meals and dishes from a variety of cuisines.

- Our book will provide a guide to the world's rich diversity of eating culture and to help explore the similarities, understand the differnces, and draw some general conclusions about our relationship with food.

- Social anthropology is the study of the everyday lives of ordinary people in all cultures, and within these cultures, one constant is food.

- The quest for food has been an essential part of the evolution of human beings,

- The quest for food accounts for the formation of cooperative hunting groups

- The quest for food serves as a source of our sociability through cooking and sharing food

- When something is designated as food underscores the cultural construction of what it is to be edible

- food becomes an "artifact". It is "cultured nature"

- Made by human ingenuity through a unique combination of ingredients using cultural techniques for acquisition and preparation.

- Food also has an aesthetic quality that is determined by culture and appraciated by that same culture

- Make make an edible assembled of what we believe to be "food"

- WHAT WE EAT IS SOCIALLY AND CULTURALLY PATTERNED AND CARRIES IMPORTANT MEANING

- Example: Japan and Rice

- There are always "staple foods" that define a cuisine. In Japan, you have not had a meal unless you have eaten rice. Without rice, there was only food, but not a meal.

- There are more than 120,000 varieties of rice in the world. In Japan, they are categorized by degree of milling, kernel size, starch content, and flavor.

- The importance of rice to culture. HERE

- The yearly quest to find Japan's best rice HERE

- Japan's culinary nationalism and "food manga" HERE (Japanese graphic novels)

- The activities surrounding food acquisition, preparation, and consumption lend themselves to cross-cultural comparison, allowing us to experience other's lives through the shared everyday experience of eating.

- Ethnography, Methodology, and Food

- Early ethnography utilized the "ethnographic present". This positioned cultures as static and bounded, despite their more complex reality.

- Today, ethnographies are more "problem focused" addressing specific aspects of people's practices.

- they are located at a specific time and place and reveal the changing dynamics of culture and society.

- they acknowledge that people, ideas, and things have always migrated (diffusion)and influenced each other and eroded the idea that there are isolated cultures with fast boundaries.

- they explore the internal and external influences on a particular place in a particular culture through time.

- culture becomes messy and dynamic -- fraught with contestation, disagreements, reconciliations, and strategies.

- They shed light on the daily experiences of individuals through the collection of "personal narratives" via "participant observation"

- Participant Observation

- tries to gain an EMIC perspective-- that of the cultural insider (a member of the culture/place) while applying the ETIC perspective of the outsider anthropologist to draw wider conclusions about how culture and society works.

- This involves everyday tasks that the fieldworker ideally can participate in. This hands on experience is essential in learning culinary traditions.

- helping with food acquisition

- preparing ingredients

- cooking

- cleaning

- Interviews (formal and informal)

- life-histories around food

- the importance of kinship and social roles to understand "gastro-politics" at the level of the household or larger society.

- memories of cooking and eating

- public discourse on food

- the many ways that people and communities talk about food.

- cultural classification

- religious and scientific menaings

- values assigned to food

- consumption rules

- identity work

- taste preferences

- comparisons can be made about different members of society in relation to food (gender, age, social class), between different cultural or ethnic groups, different places, and different times. This allows us to find THEMES.

- Cultural Relativism and Food

- you can really see the importance of the meaning of food when we notice our biases when evaluating it. Icelandic Harðfiskur and Hákarl. HERE

- food debates in American culture:

- vegetarian

- vegan

- gluten free

- keto

- kosher/halal

- organic

- non-GMO

- All foods and food traditions must be approached objectively from an anthropological perspective

- Multi-sited Fieldwork

- A reality of modern methodology is that fieldwork is rarely limited to a single site. Instead, globalization and the the food commodity chains that "examine the circulation of cultural meanings, objects, and identities in a diffuse time-space."

- Meaning: the travel of things across space and time allows for an opportunity to track their production and consumption to illuminate their cultural biographies.

- Food biographies follow commodity chains, revealing how the lives of everyone along the route are linked.

- Globalization and Food Ethnography

- Globalization is the flow of people, ideas, and things at multiple points across the globe.

- at each point in the commodity chain, people...creating local culinary outcomes. food in these different points along the chain may have very different values and meanings.

- Food is consumed locally, no matter where the food is from, and it is in the places of consumption that values and meanings are given to food as part of settled people's everyday life.

- Anthropologists are interested in how, in our everyday lives, we are connected to distant people in the commodity chain.

- Foodscapes:

- the global flow of food and cuisines as they are produced, distributed, and exchanged, and as imagined and experienced in everyone's daily lives.

- food is commodified globally.

- but locally, people can de-commodify food and invest it with local significance

- globalization can bring about a defense of the local, the revival and creation of new food traditions, and the blending of old and new ideas, things, and practices.

- Cuisines (culinary identity)

- long-term, largely nutritious food adaptations that have supported generation through time (not random),

- carry great value and meaning,

- wrought by the environment and history,

- full of emotionally connective power.

- everyday, routine, often unselfconscious cultural acts

- relevance waxes and wanes with intensity depending on the circumstances

- have powerful emotive forces - a culinary expression of a place and a people

- the culmination of the influences -

- the environment,

- the food-getting strategies,

- the organization of production through kinship, age, gender, and specialization,

- the social and political organization,

- ideology, and

- the circumstances of history and encounters with other cultures.

- example: The Middle East

- Eating as an Embodied Experience

- our experiences in the world are mediated by our bodies - through our senses we engage with one another and all other aspects of our physical environment.

- food engages with our physicality in many sensorial ways:

- gathering/harvesting

- shopping

- cooking

- eating is the most profound form of consumption we engage in, which affords it particularly potent maening in culture.